The Magnetism of Unfinished Work in Academic Medicine

Most of our best ideas live in drafts, not journals. This piece shares what happened when I circulated a rough AI-scribe write-up in our ED—and why making unfinished work visible can quietly transform your academic career.

Why Unfinished Work Is So Powerful in Academic EM

A few weeks ago, I was on a typical ED shift: crowded waiting room, hallway beds full, my brain juggling the usual mix of chest pain, belly pain, and “I haven't eaten in hours” pain.

In the middle of that, I was quietly testing something new: an AI scribe. Between patients, I’d watch it struggle with accents, miss clinical nuance, and occasionally produce something insanely useful. It was messy and imperfect, and it felt like a glimpse of where our work might be headed.

After that shift, I wrote up some thoughts and posted them here: what I tried, how I set it up, what it got wrong, and what surprised me. Nothing polished, just field notes from the front lines. Then I emailed the link to our faculty and residents, along with a few additional reflections and a preview of the academic work I was about to start.

I thought maybe one or two people would skim it and move on with their day.

Instead, my inbox lit up.

- A colleague reached out and said, “This should be a paper. Can we work on it together?”

- A resident emailed to say they couldn’t use the AI scribe yet due to institutional limitations, but they wanted to learn more about AI in medicine and saw joining the research as their way in.

- A faculty member with a background in medical education said they’d been thinking for months about how AI might shape graduate medical education, but hadn’t known where to start, until they saw this as a concrete entry point.

No one was responding to a completed project. They were responding to work that was still very much in progress.

That experience forced me to ask a question I’d been avoiding:

Why does unfinished work sometimes attract people more powerfully than finished work?

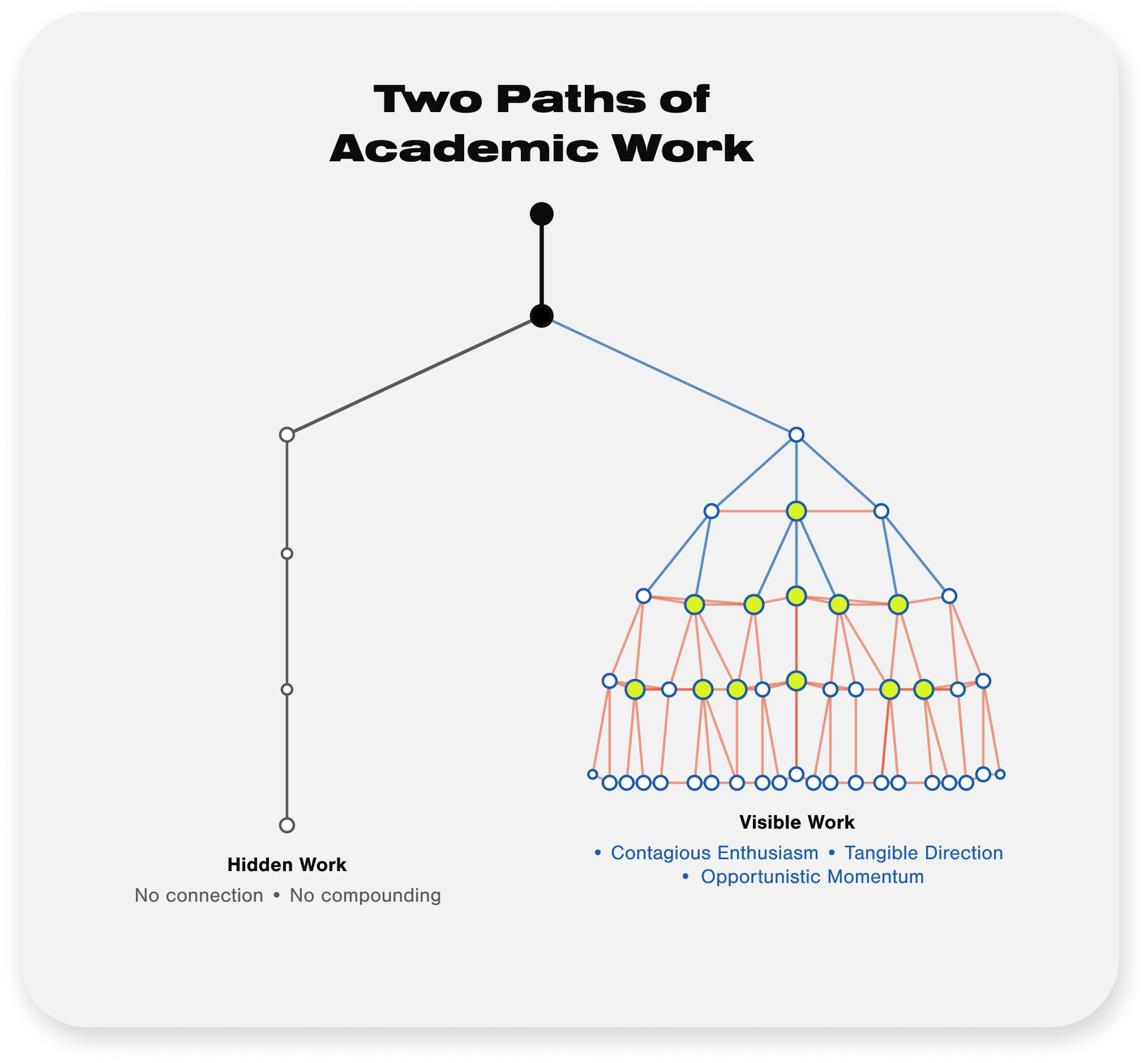

The more I’ve watched this play out, in my own projects and in academic emergency medicine more broadly, the more I’ve started to see the same three patterns:

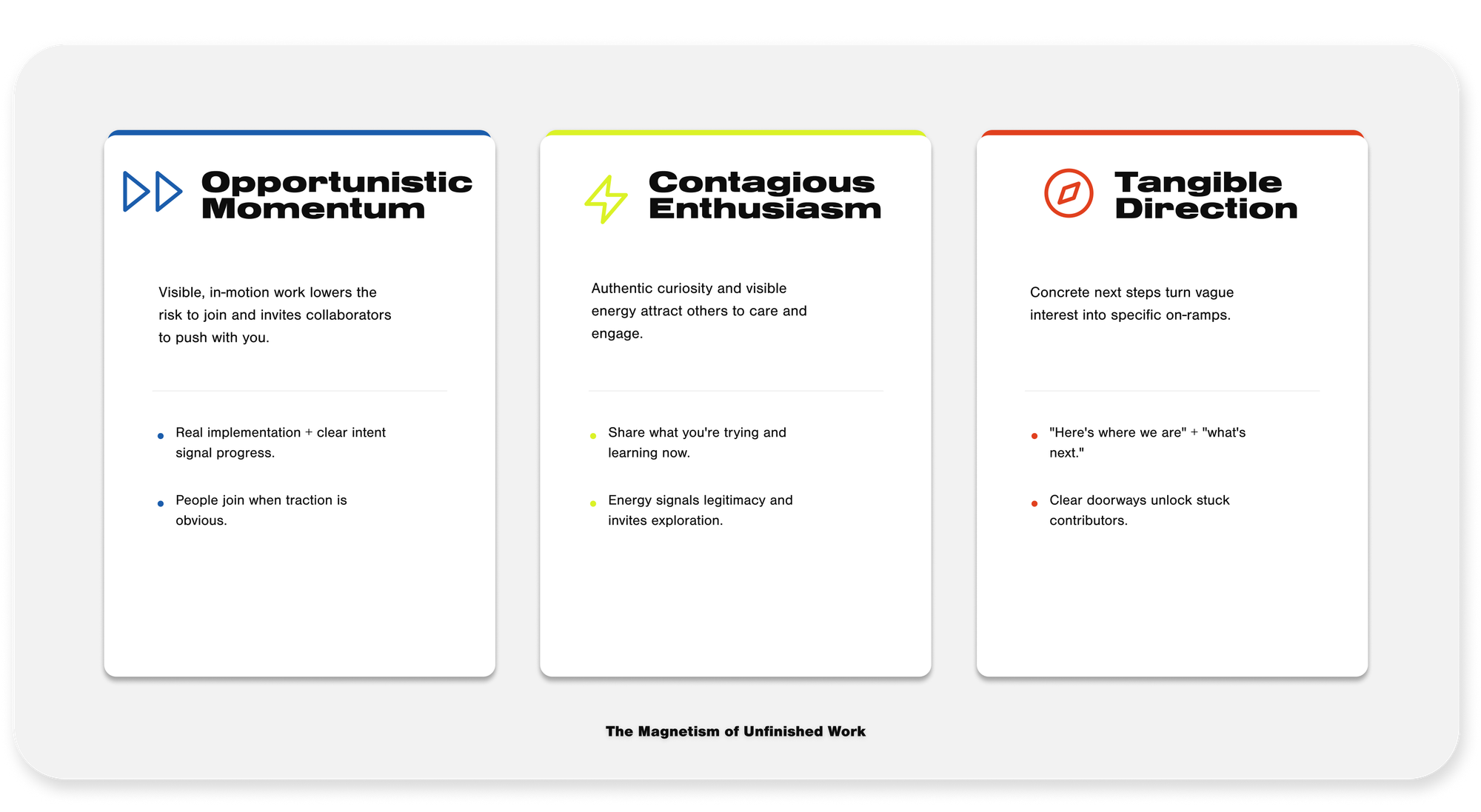

- Opportunistic Momentum: People who recognize that something is already moving and want to help push.

- Contagious Enthusiasm: People who catch your energy and use it to fuel their own curiosity.

- Tangible Direction: People who’ve been circling similar questions but finally see a way in.

Each of those colleagues saw something different in that AI scribe post. But all of them saw it because the work was visible before it was “ready.”

That’s the core argument of this piece:

In academic EM, keeping your work hidden until it’s “ready” trades away collaboration, impact, and mentorship. The real leverage comes from making your work visible while it’s still unfinished, because that’s when it has the most doorways for others to enter.

Why We Hide Our Work (and What It Quietly Costs Us)

The Myth of "Rigor Before Visibility"

If you’ve spent any time in academic medicine, you’ve likely internalized a particular script about when work is “ready” to share.

It usually sounds something like this:

- If it’s not rigorous yet, don’t share it.

- If it isn’t referenced and formatted, it’s not real scholarship.

- If you can’t defend every claim, it's better to keep it to yourself.

Underneath that is a fear most of us don’t like to admit:

What if my colleagues think this is unserious? What if I say something wrong? What if I expose how much I don’t know?

For physicians trained in evidence-based medicine, the bar for “ready to share” keeps rising. We’re taught to hedge, qualify, and, above all, wait. Wait for more data. Wait for peer review. Wait until we feel like “real” researchers or educators.

I’ve lived this.

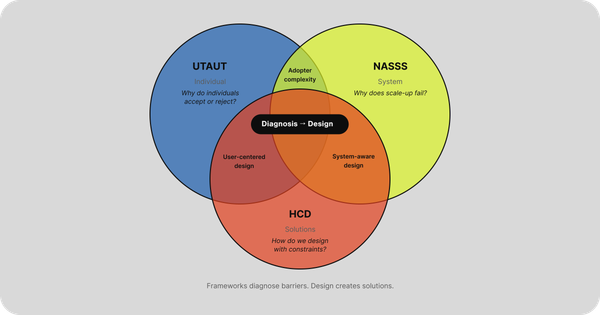

A couple of years ago, a small group of us wrote a case study manuscript on using human-centered design to improve sign-outs in the ED. From first draft to final decision, it took 18 months. I sent it to multiple journals, revised it after each round of review, reformatted figures, added references, and restructured the arguments.

Each iteration was billed as “improving” the paper. But after a while, it stopped feeling like improvement and began to feel like defensive architecture. The paper wasn’t getting meaningfully better; it was getting more fortified.

And after all that?

No actual publication.

Meanwhile, the world kept moving:

- Other groups published similar ideas.

- Preprints appeared, sparking conversations on Twitter/X, Threads and in journal clubs that I watched from the sidelines.

I told myself I was being prudent, waiting until the work was rigorous enough, polished enough, safe enough to share.

In reality, I was doing something else:

I was practicing isolation disguised as rigor.

Isolation Disguised as High Standards

The isolation felt virtuous. It felt like high standards. But it also meant no one knew what I was working on. No one could provide feedback, collaborate, or build on the work because it simply didn’t exist in their world.

For early-career academic physicians and EM residents, this instinct to hide unfinished research or QI work can quietly stall collaboration and promotion.

When we hide our work until it’s “ready,” we think we’re avoiding judgment. What we’re actually doing is guaranteeing something else:

No connection. No collaboration. No compounding.

No one can join work they can’t see.

The irony is that the same fears that keep us from sharing, “What if this isn’t good enough?”, are often best addressed by sharing earlier, not later. Because once work is visible, other people can help you refine it.

So the question becomes: why did that rough AI scribe post attract people rather than push them away?

How Unfinished Work Attracts the Right People

When I look at the messages that came in after that post, I see three different kinds of magnetism.

Opportunistic Momentum: Joining a Moving Train

The first email I received was from a colleague who basically said, “This is great. Let’s turn this into a paper.”

They weren’t interested because I’d published a randomized trial or produced flawless workflows. They were curious because it was apparent that something was already moving.

I had:

- A real implementation in a real ED.

- Concrete observations about what worked and what didn’t.

- A clear intention to keep iterating and studying it.

In other words, there was a train on the tracks, already in motion.

For faculty who need scholarly outputs, for promotion, for career progression, for their own sense of momentum, this matters. Joining something that’s already moving is safer than starting from zero. Visible work reduces the perceived risk of collaboration.

For residents trying to get involved in research, visible unfinished projects are often the most straightforward way in.

Opportunistic momentum gets a bad reputation, as if people are chasing CV lines. But often, it’s more generous than that. It’s people recognizing:

“You’re pushing on a problem I care about. If I join you, we can move it further together.”

That collaboration doesn’t happen if they never see you pushing in the first place.

Contagious Enthusiasm: Visible Energy Is a Magnet

The next message was from a resident. They’d heard about the AI scribe but couldn’t use it yet because of policy and access constraints. They were frustrated by that.

But reading the post did something different: it gave them an on-ramp.

They wrote that they wanted to understand AI in medicine more deeply, and saw research as the way to do that. They asked to be involved in the project, not because they could use the tool clinically, but because they wanted to learn about the ecosystem around it.

What drew them in wasn’t a clean methodology section or perfectly tuned stats. It was visible enthusiasm:

- “Here’s something I’m curious about.”

- “Here’s what we tried.”

- “Here’s what broke, and here’s what I still don’t understand.”

When you share that kind of real-time curiosity, it allows others to care too. It signals that this isn’t just a fad or a private obsession; it’s a legitimate space for exploration.

In EM, we’ve seen this play out over and over again through FOAMed. A handful of people get visibly excited about bedside ultrasound, airway management, or pediatric resuscitation, and suddenly:

- Residents around the world are engaging with those topics.

- Faculty at community sites are updating their practice.

- Conferences are rethinking what they teach.

The content matters. But so does the energy around it.

Enthusiasm, when it’s visible and authentic, is contagious.

Tangible Direction: Giving Stuck People a Concrete Starting Point

The third message that stuck with me came from a faculty member in medical education. They’d been thinking about AI and graduate medical education for months, how it might change assessment, simulation, and curriculum design.

They weren’t lacking interest; they were lacking a starting point.

They wrote something like: “I’ve been wanting to get involved in AI and GME, but I didn’t know where to begin. This project feels like a concrete way to start.”

That’s a tangible direction.

Unfinished work is uniquely good at providing this. Instead of presenting a polished, completed project, you’re essentially saying:

- “Here’s where we are right now.”

- “Here’s what we’ve already done.”

- “Here are the obvious next questions.”

Those next questions are the doorways.

For the med ed faculty member, the post turned “AI in GME” from an abstract interest into a specific opportunity:

- How do residents learn to supervise AI tools?

- How do we teach appropriate skepticism?

- How does documentation training change when AI enters the room?

None of those questions was spelled out in the post. But the project outline made them visible.

Again, this doesn’t happen if the only thing people ever see is the final paper, long after the interesting decisions have already been made.

From Lone Genius to Scenius in Emergency Medicine

FOAMed, Preprints, and the EM Ecosystem

We like to imagine breakthroughs happening in isolation: the researcher alone at their desk, the educator sketching a perfect curriculum, the clinician quietly refining the ideal protocol.

Real life looks different.

Brian Eno uses the term scenius to describe how creative work actually happens, not from lone geniuses, but from scenes. Clusters of people who are all exploring similar questions, who bump into each other’s ideas and make them better.

Emergency medicine already knows this, even if we don’t always name it.

- FOAMed turned scattered educators into a global network.

- Blogs and podcasts turned local teaching points into shared resources.

- During COVID, preprints and rapid updates turned individual observations into living protocols that evolved in real time.

The “scene” became the engine of change.

Why Visibility Beats Isolation for Innovation

Showing your work, especially when it’s unfinished, is how you participate in that scene instead of just consuming it. It’s how you shift from:

- “I read cool things other people are doing,” to

- “I’m part of the conversation about where this is going.”

And yes, sometimes that visibility stings. I’ve shared things that have drawn criticism. I’ve had people question whether something was rigorous enough or worry that it would be misinterpreted.

But even those moments have been instructive. They’ve forced me to:

- Clarify my thinking.

- Tighten my language.

- Build guardrails for how and what I share.

I’m not arguing that you should throw everything onto the internet and see what happens.

I’m arguing that total secrecy is rarely the safest path either.

How to Show Your Work Safely in Academic EM

If you’ve read this far, you might be thinking:

“Okay, fine. But I don’t want to get fired, sued, or quietly blacklisted.”

Fair.

The fear of sharing is not purely emotional. There are real constraints:

- Institutional social media policies.

- Medico-legal concerns about cases.

- Cultural norms in your department.

- Promotion committees that still only count traditional outputs.

So how do you navigate that without retreating into isolation?

Internal vs External Visibility

Not all visibility is public.

If your institution is wary of social media or blogs, start with internal scenius:

- A short write-up shared on your faculty/resident email list.

- A post in your department’s Slack, Teams, or WhatsApp group.

- A five-minute “here’s what we’re experimenting with” blurb at conference.

- A one-page “field report” on a new workflow or teaching tweak.

These are all ways to show your work. They still create opportunities for:

- Residents to say, “Can I help with that?”

- Colleagues to say, “We tried something similar—here’s what happened.”

- Leaders to see what you’re building and connect you with resources.

If you have the freedom and appetite for external sharing, that might look like:

- A post on your personal or department blog.

- A thread on Threads/Twitter/X summarizing an experiment.

- A short reflection on LinkedIn about implementation challenges.

- A guest post or appearance on an existing FOAMed platform.

The key is not where you share first. It’s that your work stops living exclusively inside your own head and your hard drive.

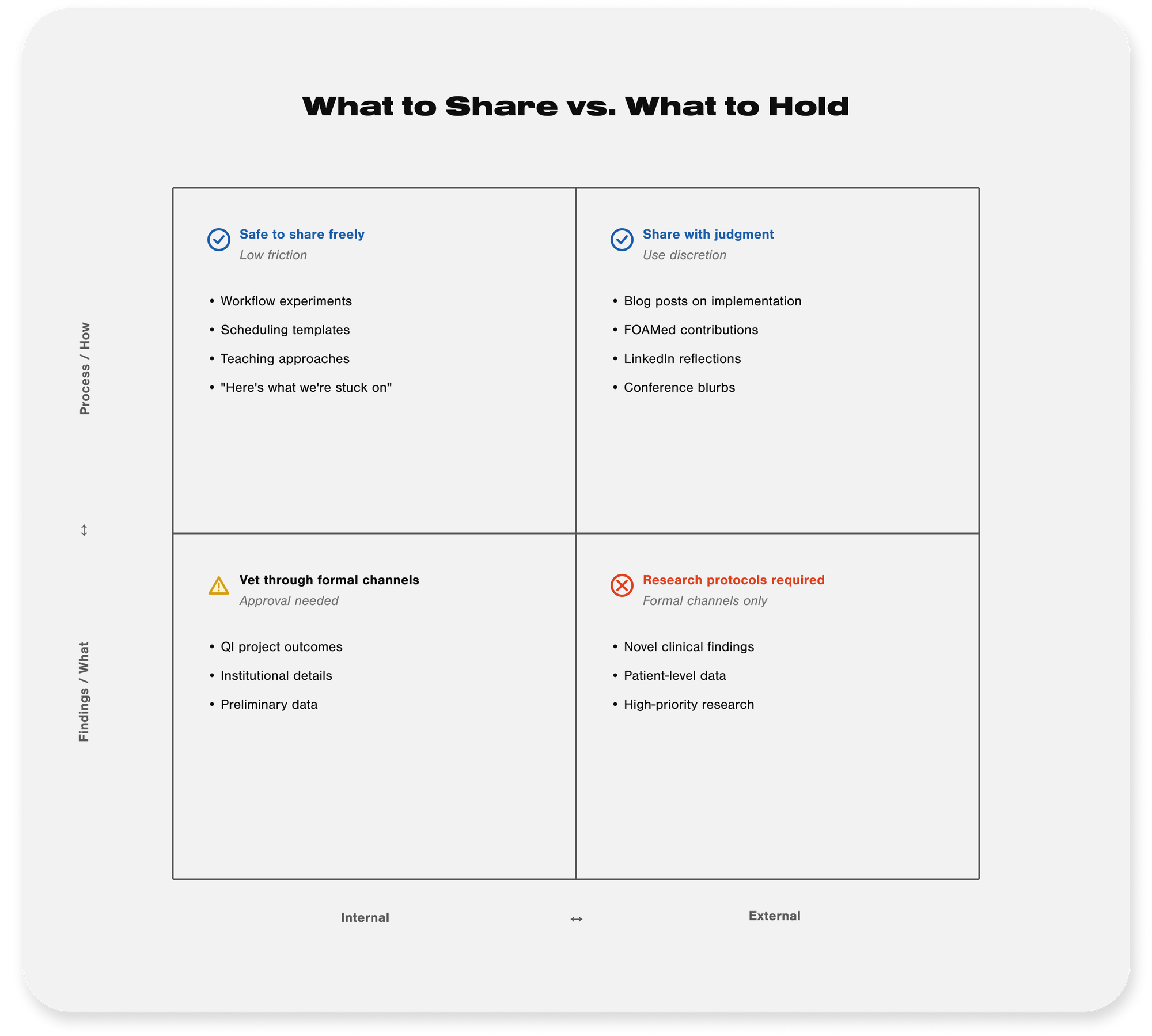

What to Share (and What to Hold)

You don’t have to put your entire research pipeline on display. In fact, you absolutely shouldn’t.

A simple rule that’s helped me:

If it’s about how you’re working, it usually belongs in the open.

If it’s about what you found clinically, treat it like research.

In practice, that means:

Reasonable to share (internally or externally, with judgment):

- Workflow experiments and implementation details.

- Scheduling innovations or templates.

- Teaching approaches, curricula, and assessment tools.

- Negative results from QI projects that will never see a journal.

- Questions you’re actively wrestling with: “Here’s what we’re stuck on.”

Best kept in formal channels until vetted:

- Novel clinical findings and outcome data.

- Anything involving patient-level information.

- Institutional details that could create risk or misinterpretation.

- Ideas where priority really matters (e.g., early-stage, high-impact trials).

Most of what we learn in day-to-day academic EM, the things that actually change how we practice and teach, never make it into journals.

That “lost 80%” is precisely where showing your work is most valuable.

Visibility as Leverage, Meaning, and Role Modeling

Letting Your Work Compound Over Time

Early in your career, it’s easy to fall into the trap of thinking:

“If I just keep working harder, more shifts, more lectures, more projects, I’ll get where I want to go.”

There’s some truth to that. But there’s also a ceiling. You can only trade so many hours for so long before you hit the limits of time, energy, or sanity.

Visible work operates differently.

When you write a post about an experiment, share a rough prototype, or outline what you’re learning, that work keeps moving without you. It builds a kind of compound interest:

- A resident reads it and joins your project.

- A faculty member at another site adapts your idea and invites you to collaborate.

- A trainee uses your post as the starting point for their own scholarly work.

A single rough piece of work can become:

- A multi-year stream of mentorship.

- A series of abstracts or publications.

- Changes in practice you’ll never see directly.

Becoming a Researcher by Sharing in Public

There’s also an identity component.

I used to think I needed to be a researcher or an educator before I could share. That once I had enough titles, experience, or publications, I’d be “allowed” to talk about what I was doing.

It’s backwards.

You don’t share because you’re a researcher.

You become a researcher by sharing what you’re doing, repeatedly, in public (or at least in community).

The same is true for being an educator, a leader, and a systems thinker.

Modeling the Process for Trainees

And for trainees and junior faculty watching you, the difference matters. They don’t just need to see your CV. They need to see:

- The half-baked ideas.

- The projects that changed direction.

- The workflows that failed and why you kept going.

That’s how they learn what’s actually possible.

Practical Experiments: What “Showing Your Work” Can Look Like This Week

This all sounds nice in theory. But what does it look like in the constraints of real EM life?

Here are a few role-specific experiments you could try this week.

If You’re Early-Career Faculty

Pick one small thing you’re tinkering with, a new sign-out template, an ultrasound teaching tweak, a flow change you’re testing on nights.

Write 150–300 words and share it somewhere internal:

- What you hoped would happen.

- What actually happened (good, bad, or mixed).

- One question you still have.

End with an invitation:

- “Has anyone tried something similar?”

- “Who else is interested in working on this?”

You’re not branding yourself. You’re opening a door.

If You’re Mid-Career

Think of a QI project or teaching practice you’ve quietly honed for years:

- How you manage bouncebacks.

- How you run your difficult case debriefings.

- How you structure senior resident autonomy.

Draft a short “this is how we actually do it” piece.

Share it internally. Then, if it seems to resonate:

- Turn it into a blog post or FOAMed resource.

- Build a workshop or abstract around it with a resident or student as co-author.

The key move is this: bring juniors into the middle of the work, not just the clean tail end.

If You’re Senior Faculty

You’re sitting on a mountain of tacit knowledge, the kind that never fits neatly into a paper.

Choose one piece:

- How you talk to families on the worst day of their lives.

- How you navigate conflict with consultants.

- How you’ve stayed in EM for 20 or 30 years without burning out completely.

Share a rough version:

- A one-page memo.

- A brief talk at conference.

- A short post on an internal platform.

Name it explicitly as in-progress:

“This isn’t a perfect recipe. It’s simply how I do this today. Please borrow it, break it, and improve it.”

That act alone can change how the next generation sees what’s possible.

Sharing as Generosity, Not Self-Promotion

It’s easy to frame all of this as self-promotion. That’s partly why we resist it.

But the more I sit with it, the more I think this is the wrong frame.

Those colleagues who reached out after the AI scribe post weren’t responding to a brand, a perfectly executed study, or a finished product. They were responding to:

- Visible curiosity.

- Visible effort.

- Visible invitation.

They saw work that was alive and evolving, not sealed and done. They recognized opportunistic momentum worth joining, contagious enthusiasm they wanted to borrow, and tangible direction that let them finally take a step.

Sharing your work, especially when it’s unfinished, isn’t about saying, “Look at me.”

It’s about saying:

“Here’s something I’m learning that might help you. Here’s a path you can join if you want to.”

So here’s the challenge:

- Identify one thing you’re currently tinkering with, a research question, a clinical innovation, a teaching experiment.

- Write 5–10 sentences about it: what you’re trying, what you’re learning, and what you still don’t know.

- Share it somewhere a real colleague can see it this week.

Not because it’s ready.

Because you are.

The people who need to see your work already exist. They’re in your ED, your division, your residency, your broader community.

They can’t connect with what they can’t see.

Show them what you’re working on, while it’s still in motion.

That’s where the magnetism begins.