Diagnose Before You Design

Enthusiasm at the demo. Excitement in the pilot. Silence six months later. Two frameworks reveal why healthcare tech fails and what to do before designing solutions.

The Pattern

Here's a pattern I keep seeing: Enthusiasm about the idea. Excitement during the pilot. Silence six months after rollout.

In my early research on AI adoption in emergency medicine, I've noticed something interesting. Some physicians have tried the technology once, maybe twice, then stop. Others would push through initial friction and become regular users. The difference wasn't the technology. It was everything around it.

This pattern plays out across healthcare. We build beautiful solutions to problems we haven't fully understood. We celebrate pilot successes that evaporate at scale. We blame "resistance to change" when implementation fails, as if physicians simply woke up one day and chose stubbornness.

But what if the problem isn't resistance? What if we're designing before we've diagnosed?

Two frameworks have changed how I think about this. They don't tell you what to build. They tell you where to look and why adoption happens (or doesn't). And they've become, for me, the essential first step before any design work begins.

What We Get Wrong

Healthcare has a deeply ingrained belief: build it well, and they'll use it. If the technology works, if it's objectively better, adoption should follow naturally. When it doesn't, we reach for familiar explanations. Insufficient training. Not enough buy-in from leadership. Clinicians who just don't like change.

These explanations feel satisfying. They give us someone to blame and something to fix. More training sessions. More emails and memos. More mandatory compliance.

But here's the uncomfortable truth: most implementation failures aren't execution problems. They're understanding problems.

We treat implementation as the final step in a process. The technology is built. The contract is signed. Now we just need to get everyone to use it. This framing treats adoption as an afterthought rather than a design challenge in its own right.

The gap between technical success and human adoption is enormous. A tool can work perfectly in a controlled demo and fail completely in the chaos of a busy emergency department. It can improve outcomes in a pilot and create new problems at scale. It can be objectively superior by every metric and still sit unused.

This gap exists because adoption happens at multiple levels simultaneously. Individual clinicians make personal decisions about whether a technology fits their workflow. Teams negotiate how to integrate new tools into shared processes. Organizations balance competing priorities and limited resources. Health systems navigate regulations, reimbursement, and political considerations.

Most implementation strategies address one level while ignoring the others. That's why they fail.

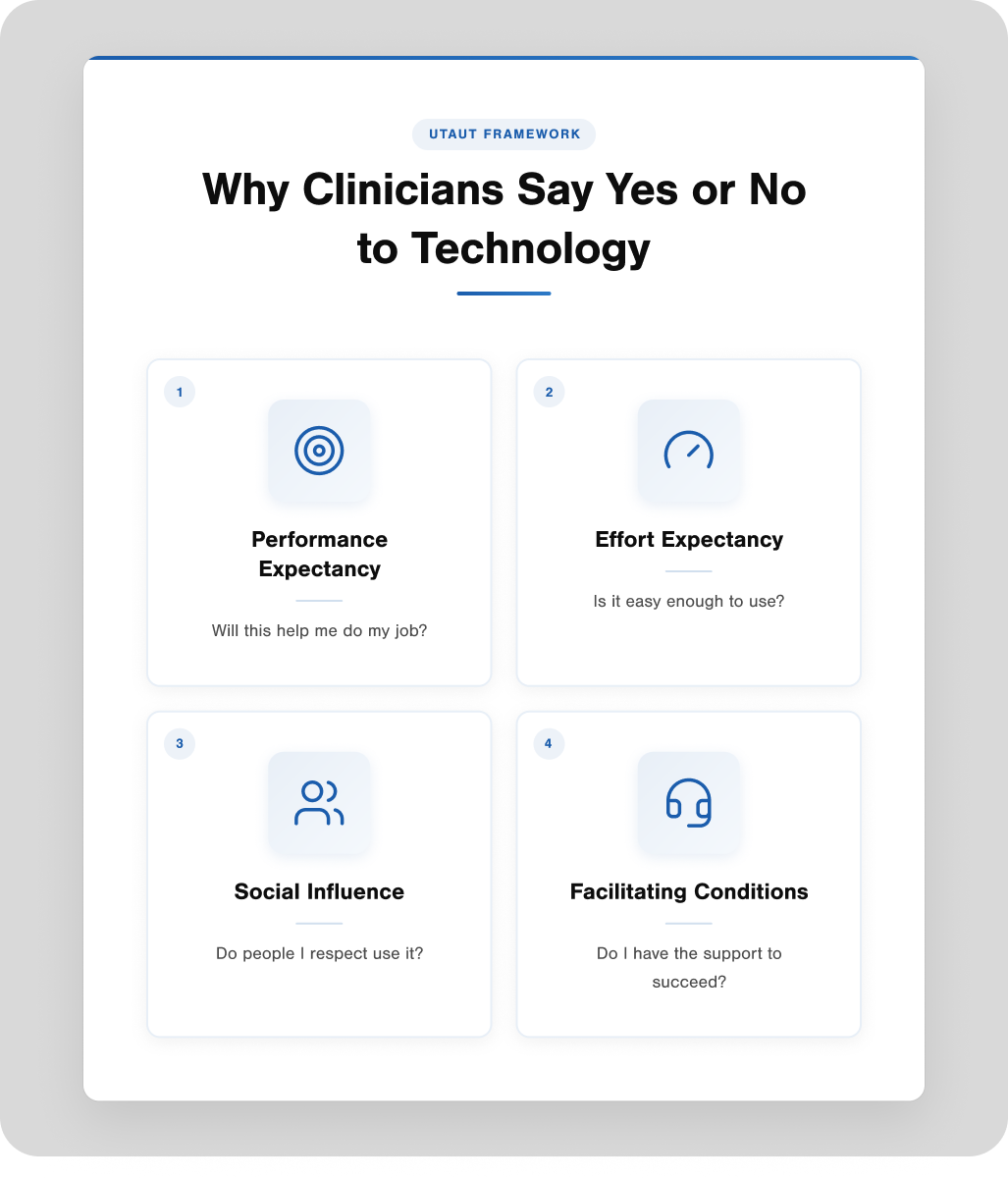

UTAUT: The Individual Level

The Unified Theory of Acceptance and Use of Technology sounds exactly like what it is: an academic framework synthesized from decades of research on why people adopt (or reject) new tools. UTAUT emerged in 2003, when Venkatesh and colleagues combined eight technology acceptance models into a unified theory.

Despite the academic packaging, UTAUT answers a practical question: Why does an individual say yes or no to technology?

Four factors drive the answer.

Performance Expectancy: is the most powerful predictor. Simply put: Will this help me do my job better? Not "is this objectively better" but "do I believe this will improve my actual work?" There's a crucial difference. A technology might reduce documentation time by 40% in studies, but if the physician doesn't believe it will help them specifically, in their specific context, adoption won't happen.

Effort Expectancy: captures the friction question. How hard will this be to use? Healthcare workers already operate under an enormous cognitive load. Every additional click, every extra screen, every moment of confusion gets weighed against the potential benefit. If the effort feels too high relative to the payoff, the answer is no.

Social Influence: matters more than technologists usually admit. Do the people I respect use this? Is my department head advocating for it? Do my colleagues think I should? We like to imagine adoption decisions as purely rational cost-benefit analyses. They're not. We're social creatures who take cues from our peers and leaders.

Facilitating Conditions: address the infrastructure question. Do I have the support, training, and resources to actually use this effectively? A brilliant technology becomes worthless if the WiFi is unreliable, the help desk takes three days to respond, or nobody taught me what to do when it breaks.

These four factors explain about 70% of the variance in whether someone intends to use a technology and about 50% of the variance in actual use. That's remarkably good predictive power for something as complex as human behavior.

Here's what UTAUT reveals in practice. In my research on AI scribes in emergency medicine, I noticed clear threshold effects between different user groups. Some physicians might try the technology briefly and stop. Others might push past initial difficulties and become regular users. UTAUT could help explain why: the trialers may experience high effort expectancy without sufficient performance expectancy to push through. The regular users may either find the effort lower, the benefit higher, or have stronger social and structural support.

But UTAUT has limits. It focuses on the individual decision at a point in time. It treats the technology as a fixed variable. And it doesn't account for the organizational complexity, policy environment, or system-level factors that often determine whether good individual adoption translates into sustainable implementation.

That's where we need a different lens.

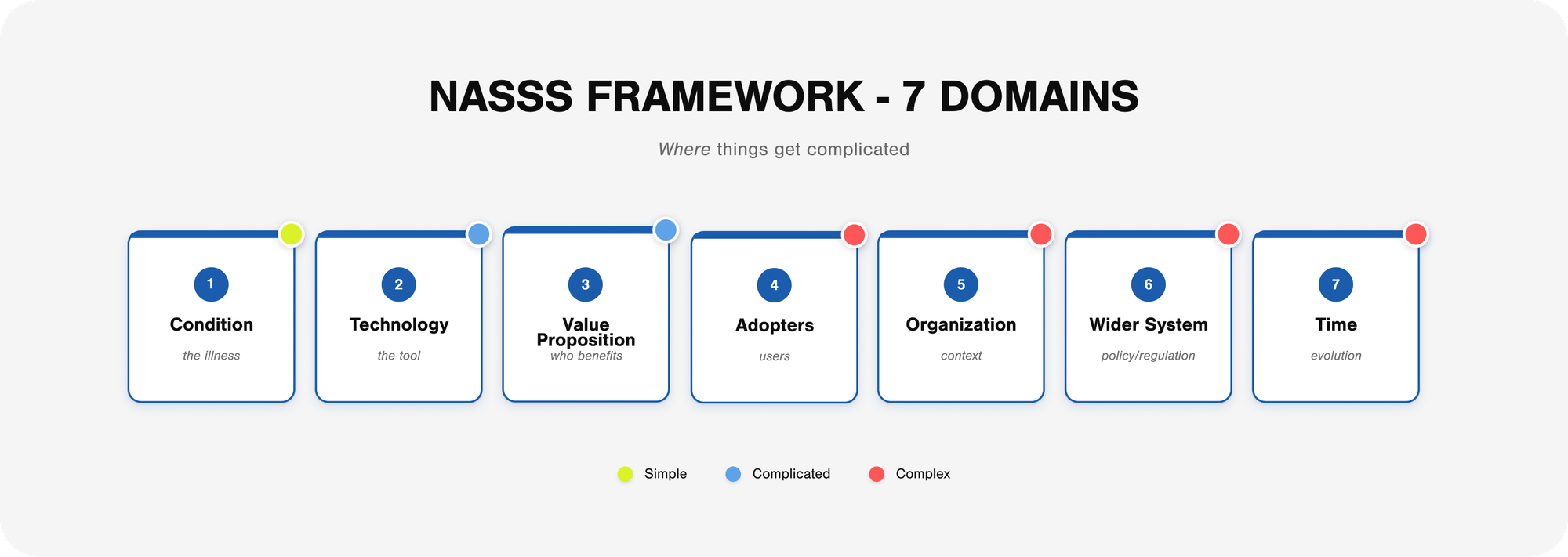

NASSS: The System Level

If UTAUT explains why individuals adopt technology, NASSS explains why good technology fails at scale.

The Non-adoption, Abandonment, Scale-up, Spread, and Sustainability framework emerged from Greenhalgh and colleagues' research on the implementation of health technologies. They studied six different technology programs in detail, spending over 400 hours in ethnographic observation, conducting 165 interviews, and analyzing 200 documents. What they found was a consistent pattern: programs with complexity in multiple domains rarely get beyond the pilot phase.

NASSS maps complexity across seven domains.

The Condition: is the illness or health issue being addressed. Is it well-defined or poorly understood? Predictable or variable? A technology designed for acute appendicitis faces a simpler adoption path than one designed for multi-morbid chronic disease management.

The Technology: itself has its own complexity profile. Does it work reliably? Does it integrate with existing systems? Does it require a significant behavior change to use? Some technologies are plug-and-play. Others demand a fundamental workflow redesign.

The Value Proposition: is where many healthcare innovations fail. The value has to work for multiple stakeholders: the patient, the clinician, the organization, and the payer. A technology can be valuable to patients while being financially unviable for hospitals. It can improve clinical outcomes while creating an administrative burden. Getting value alignment across stakeholders is harder than it sounds.

The Adopter System: includes everyone who needs to change their behavior: clinicians, staff, patients, and caregivers. This is where UTAUT fits within NASSS. The individual acceptance factors matter, but they exist within a broader social and professional context.

The Organization: has its own complexity. What's the culture around innovation? How are resources allocated? How does decision-making work? Is there capacity to support implementation? Organizational readiness can make or break adoption.

The Wider Context: encompasses policy, regulatory requirements, professional standards, and the broader political economy of healthcare. Technologies can succeed within organizations but still fail when they encounter billing limitations, liability concerns, or regulatory gaps.

Embedding and Adaptation Over Time: acknowledges that implementation isn't an event; it's a process. Technologies need to evolve. They need local adaptation. They need ongoing attention and refinement. The question isn't just "will they adopt it?" but "will they keep using it, adapting it, and improving it?"

The key insight from NASSS is that complexity compounds. If you have simple challenges in most domains, implementation is relatively straightforward. If you have complicated challenges in some domains, it's harder but doable. But if you have complex challenges in multiple domains simultaneously, scale-up rarely succeeds.

Video telehealth offers a good example. Many telehealth pilots were successful during COVID-19. Individual users accepted the technology (UTAUT factors were favorable). But scale-up and sustainability have been uneven since then because the challenges compound across NASSS domains. Reimbursement policies (wider context) interact with workflow integration (organization), patient access issues (condition), and clinician preferences (adopters) in ways that are hard to predict or control.

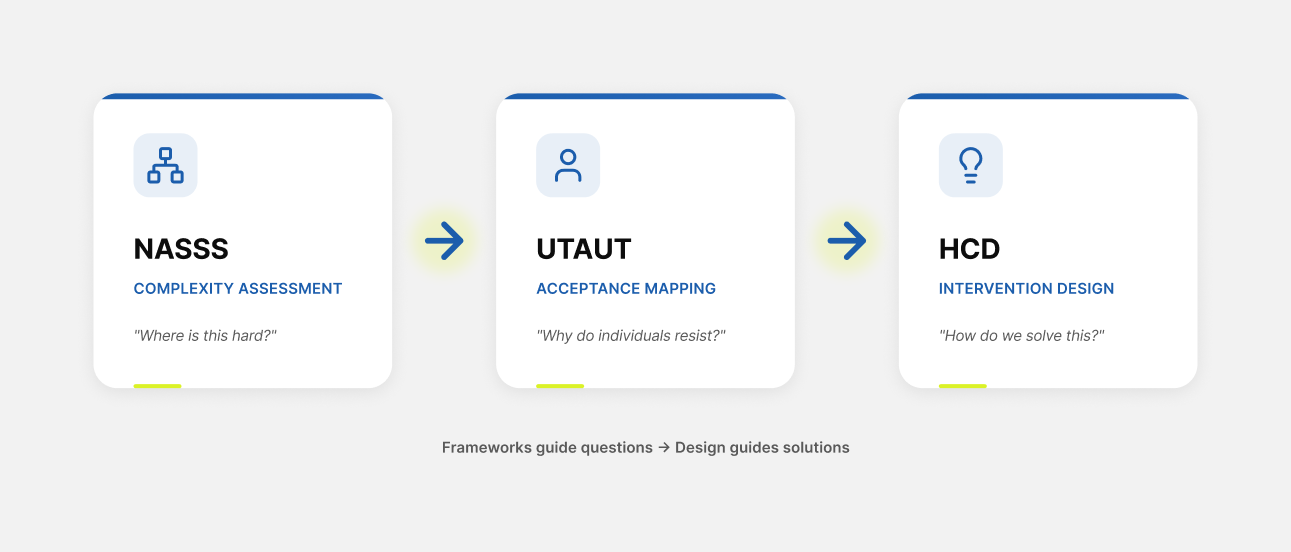

The Relationship with Design

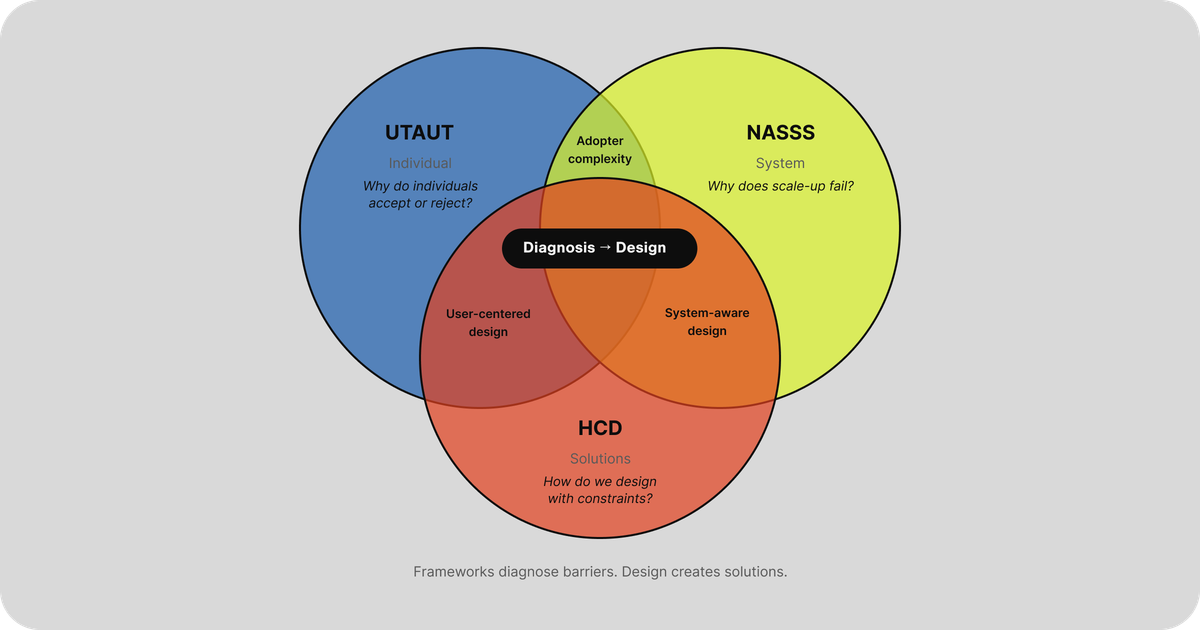

So where does design fit?

Think of it like medicine. UTAUT and NASSS are diagnostic tools. They help you understand what's happening and why. Human-centered design is the treatment. It helps you create solutions.

This distinction matters. Frameworks and design do different things.

| Frameworks (UTAUT, NASSS) | Human-Centered Design |

|---|---|

| Diagnostic orientation | Generative orientation |

| Ask: Why does this happen? | Ask: How might we solve this? |

| Output: Understanding | Output: Solutions |

| Analytical mode | Creative mode |

| Explains existing patterns | Creates new possibilities |

The relationship is sequential and complementary. You need a diagnosis before a treatment. You need understanding before solutions.

Healthcare is actually good at diagnosis. We have quality improvement methodologies, root cause analyses, and process mapping tools. The problem is that we often stop there. We identify the barriers, catalog the challenges, and write the report. And then we deploy anyway, hoping the analysis somehow translates into successful adoption.

Or we skip diagnosis entirely and jump straight to solutions. Someone has an idea. Someone builds a prototype. Someone gets excited about the demo. And six months later, we're back to wondering why nobody uses it.

The power of combining frameworks with design is that analysis becomes actionable. Framework findings don't just explain patterns; they also shape them. They become design constraints. They tell you what problems your solution needs to solve.

| Framework Finding | Design Constraint |

|---|---|

| Effort expectancy is too high | Reduce cognitive load |

| Social influence is low | Build peer visibility into rollout |

| Facilitating conditions are weak | Design for inadequate support |

| Organizational complexity is high | Design for local adaptation |

| Value proposition unclear to payers | Make ROI visible in the product |

Healthcare's failure mode is treating framework findings as barriers to overcome rather than constraints to design in. When adoption barriers are identified, the default response is training, mandates, and incentives. These approaches treat the barriers as problems to push through rather than signals pointing toward design opportunities.

Here's the uncomfortable truth: when a hospital "rolls out" new software with a two-hour training and a PDF quick guide, that is a design decision. It's just bad design by default. Healthcare would never diagnose a patient and then simply hope for the best. But that's exactly what happens with technology implementation.

The On-Ramp to Design Thinking

There's a practical problem with bringing design thinking into healthcare. Design vocabulary sounds fuzzy to healthcare leaders trained in evidence-based medicine. "Empathy" and "ideation" and "co-creation" can trigger skepticism in environments built on randomized trials and statistical significance.

Frameworks solve this problem. They create an on-ramp.

When you walk into a meeting with hospital leadership and say, "We need to do design thinking," you might get polite nods and zero budget. When you walk in with a NASSS complexity assessment showing exactly where implementation is failing across seven domains, backed by Greenhalgh's research and published evidence, the conversation changes.

Frameworks make complexity visible in ways that resonate with healthcare's epistemological preferences. They use structured assessment. They have evidence bases. They produce analyzable outputs. They speak the language that healthcare trusts.

And once the complexity is visible, the need for design becomes obvious. You can't train your way out of a fundamental workflow mismatch. You can't mandate your way past a broken value proposition. You can't incentivize your way through inadequate infrastructure.

The analysis reveals that what's needed isn't more implementation effort. It's design. And then design thinking enters through a door that healthcare opened for itself.

Practical Integration

How might these frameworks actually be used in practice?

One potential approach involves three sequential phases.

Phase 1: NASSS Complexity Mapping. Before investing significant resources in implementation, map the complexity landscape. Walk through each domain and ask: Is this simple, complicated, or complex? Where are the likely failure points? What domains need attention before rollout?

This phase would likely reveal that implementation challenges exist far from the technology itself. The technology might be simple, but the organizational context is complex. Individual adopters might be favorable, but the broader policy environment creates barriers.

Phase 2: UTAUT Acceptance Assessment. Once the system-level complexity is understood, the focus shifts to individual acceptance factors. Who are the different user groups? What are their performance and effort expectations? What social dynamics influence adoption? What infrastructure exists to support them?

This phase would likely reveal that different user segments face different barriers. Research on AI scribe adoption, for example, suggests that non-adopters, trialers, regular users, and power users each encounter distinct challenges. Understanding these differences could point toward differentiated design strategies.

Phase 3: HCD Intervention Design. Now design can begin. But it's not design in a vacuum. It's design that targets the specific barriers identified in Phases 1 and 2. The diagnostic analysis generates the design constraints.

The framework findings guide the design questions. If effort expectancy is the primary barrier, how might we reduce cognitive load? If organizational complexity is high, how might we design for local adaptation rather than uniform deployment? If the value proposition is unclear to payers, how might we make ROI visible in the product itself?

What Frameworks Can't Do

A framework is not a formula. UTAUT and NASSS have real limitations.

They won't tell you what to build

They diagnose problems; they don't generate solutions. You still need the creative, generative work of design to move from understanding to action.

They can create analysis paralysis

It's possible to spend so much time assessing complexity that you never actually build anything. Perfect understanding of why adoption fails doesn't help anyone if you never try to make it succeed.

They assume technology is the answer

Both frameworks start with a technology and analyze adoption. They don't ask whether technology is the right intervention in the first place. Human-centered design at its best questions whether a technical solution is even needed.

The map is not the territory

Frameworks are models. Models simplify reality to make it tractable. Every framework misses something. Real implementation involves messiness, contingency, and emergence that no diagnostic tool fully captures.

The balance is: understand enough to act intelligently, then act. Iterate. Learn from what happens. Adjust.

Start Here

If you want to bring design thinking to healthcare, you need to speak the language healthcare trusts. Frameworks give you that vocabulary.

But never forget design's superpower: making things. Analysis that doesn't lead to creation is just commentary. The goal isn't to understand implementation perfectly. It's to understand implementation well enough to design better solutions.

Here's where to start:

Learn the frameworks. Read Greenhalgh's NASSS paper. Understand UTAUT's core constructs. Get comfortable with the vocabulary.

Map one challenge. Pick a technology implementation you're involved with. Walk through NASSS domains. Consider UTAUT factors for different user groups. Where is complexity hiding? Where are the real barriers?

Design solutions. Take one barrier you identified and ask: How might we design around this? Not "how do we push through it" but "how do we solve it?"

Healthcare is good at diagnosis. It's bad at recognizing that what comes next is design. And if you don't design intentionally, you design badly by default.

The frameworks aren't the destination. They're the on-ramp. Use them to understand where design is needed. Then do the design work.

Act intelligently within uncertainty. That's all any of us can do.