The Art of Conveying Health Information

Stop treating presentations like information transfer. Start designing them for behavior change. Here's how emergency medicine can lead healthcare communication transformation.

Doceré; to teach. The latin root for doctor.

Medicine is built on teaching. See one, do one, teach one. We learn frameworks for diagnosis, protocols for procedures. No matter your role, as a physician, you will teach someone, something.

While teaching has evolved from bedside Grand Rounds to protected didactic time—Wednesday mornings in emergency medicine—we've maintained teaching as our top priority.

Yet while we help residents learn how to make rapid medical decisions on shift in the emergency department, we often fail to teach them how to communicate the health information they wish to share with their patients, colleagues and future learners. Instead of teaching best practices for presenting and modeling those principles, we use presentations as data-dumps; prioritizing a certain comprehensiveness while sacrificing clarity or effectiveness.

We wouldn't design a medication without thinking about dosing, interactions, and delivery mechanisms. But we design our communications as if information transfer happens by magic. And we all pay the price. Picture this: It's 7 AM, change of shift. You've got 12 patients to sign out in 20 minutes. Patient in bed 8 has 'chest pain, discharge home after the second trop.' But you don't mention the subtle EKG changes you were watching, or that the patient's pain gets worse with exertion now. Three hours later, the day physician is calling cardiology for an emergent cath. Or the M&M where we spend 30 minutes reviewing every lab value but run out of time before discussing how to actually prevent the next case.

What if we approached these communication challenges the same way we approach clinical protocols - with systematic design, user testing, and continuous improvement? What if we started treating communication as a design problem?

What's actually broken

Let's take a look at four avenues in which we must effectively convey health information in emergency medicine and how they're being hindered by poor communication. Each represents a failure to design communication for its intended purpose - to change minds, create mental models, and drive behavior.

M&M Presentations

We've all sat through M&Ms where we spent 30 minutes on timestamps and lab values, only to run out of time before discussing how to actually prevent similar cases. The most common misstep I see, is a tendency to focus on presenting all of the detail of a case, every lab value, timestamp, and event in the patient's care. By doing this, we often push the conversation to focus on the minutia, while missing the bigger questions that drive cognitive errors, systems issues, or workflow missteps that cause patients' poor outcomes than the minor details along the way. We're designing for documentation instead of prevention.

Case Presentations

By "presentation," I’m referring to the classic lectures we’re all familiar with. Picture yourself settling into weekly educational didactics, coffee in hand, as the presenter kicks things off with a brief case to ground the rest of the talk in real-world practice. Good—making it practical. After working through a differential diagnosis for the case, the presenter moves on to summarize the relevant chapter from Tintinalli’s or Rosen’s, thoroughly covering the pathology or disease in question. It’s comprehensive, evidence-based, and contains the best information we have on the topic. Yet, despite the presenter’s excellent review, they’ve missed the underlying issue. Three weeks later, you're seeing the same missed diagnosis in the ED because nobody walked away thinking 'I need to change how I approach these cases.' We're designing for content delivery instead of mindset change.

QI Presentations

Quality improvement is the commitment to seeing what goes wrong as opportunities for change, to do better next time. Picture the monthly QI presentation: 15 slides of door-to-antibiotic times, length-of-stay metrics, and patient satisfaction scores. Meanwhile, you're thinking 'My last sepsis patient waited 3 hours just to get a bed.' We're measuring everything but changing nothing. We're designing for measurement instead of improvement.

Patient Signouts

We've all been there - 7 AM signout, 12 patients to hand off, and somehow you spend 5 minutes explaining why you ordered each lab for bed 8 instead of the 30 seconds needed to say 'Watch for evolving STEMI - something's not right with this chest pain.' Failure to strike the appropriate balance between comprehensive and concise leads to errors; missed pending labs, wrong disposition decisions, delayed procedures. We're designing for information transfer rather than creating mental models.

The Treatment Plan: A New Framework

Emergency medicine is built on creativity, experimentation, and a get-it-done attitude. Our specialty thrives on rapid innovation and evidence-based practice, making us natural leaders in evolving communication—but we need the right tools to do it well.

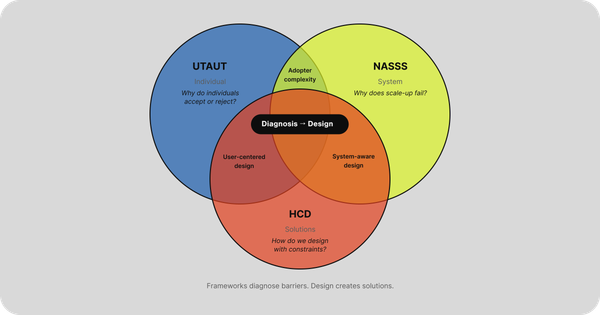

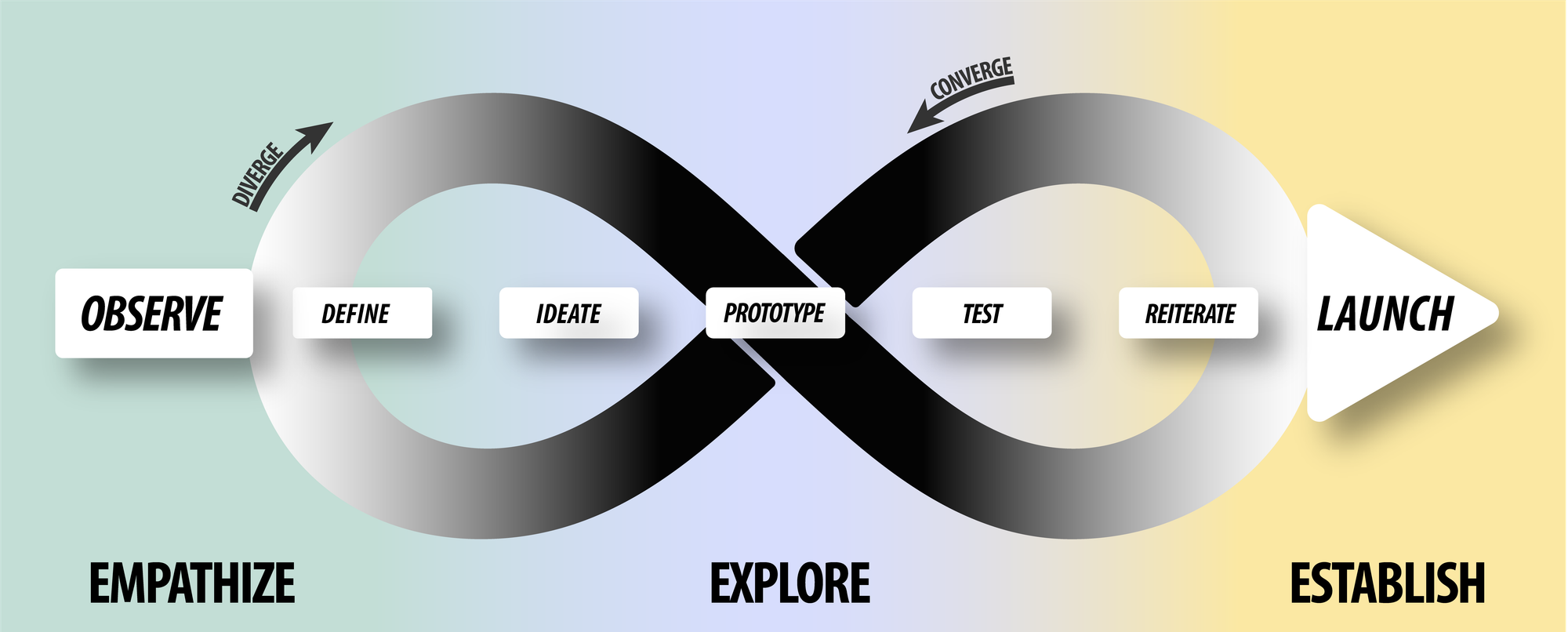

Human-centered design (HCD) is a mindset and set of skills applied to a particular framework, which seeks to find solutions to complex problems that are feasible, sustainable, and most importantly, desirable. HCD ensures that you are building the right thing, before you work on building it right. What is a design mindset?

In the book Designing your Life, Bill Burnett and Dave Evans introduce what they feel are five key mindsets for design:

- Curiosity

- Bias to action

- Awareness

- Radical collaboration

- Re-framing

Does that sound familiar? This is the epitome of an emergency medicine physician. The necessary foundation is already in place.

The design process is simple: understand the problem deeply before jumping to solutions. In EM terms, get the right differential before choosing treatment.

So how do we apply this thinking to EM education?

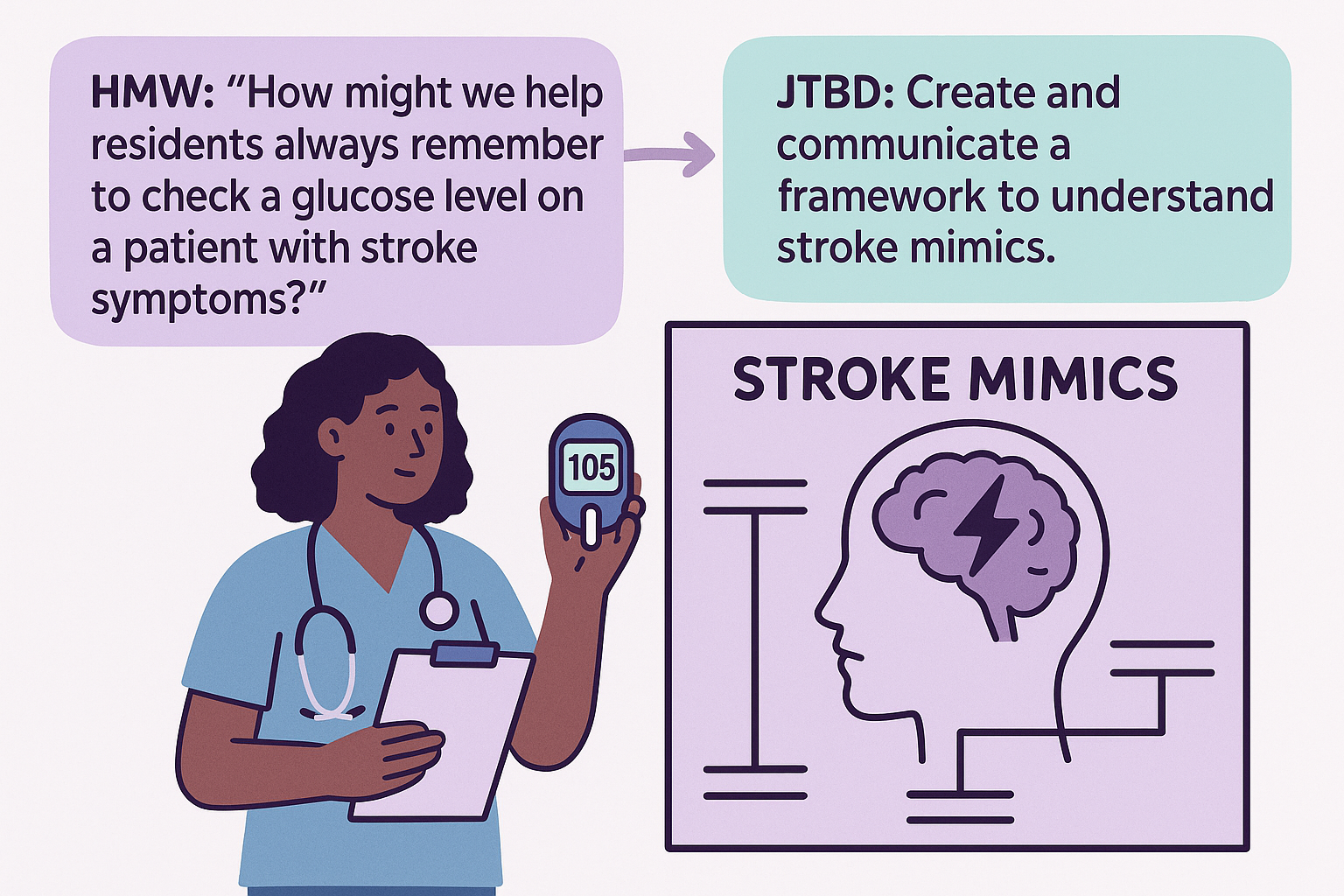

The key is reframing your presentation challenge as a 'how might we' question. Instead of 'Residents keep missing stroke mimics,' ask 'How might we help residents always check glucose in stroke-like symptoms?' Instead of 'Medical students take forever with histories,' ask 'How might we teach focused history-taking?'

This shift from problem-focused to solution-focused thinking is what designers call 'jobs-to-be-done' - understanding what you actually want to accomplish. Your presentation's job isn't to download information; it's to change behavior. When preparing any didactic, start with: 'What specific change am I trying to create?' That becomes your design challenge.

This shift from 'how do we present all the information?' to 'how might we create the change we want?' is the foundation of a systematic approach we'll explore in this series. Just like we don't dump an entire ACLS protocol on a new intern at once, we'll build this presentation framework step by step.

The process involves five specific mindset shifts, a practical three-part framework, and yes - AI tools that can help you develop and practice presentations more effectively than traditional approaches.

But here's what you can do right now...

I want you to audit the next presentation you are set to give. Whether it's for M&M, resident didactics, or a weekly QI presentation to your group, reframe your goal around the behavior you are trying to change. Ask yourself "what change am I trying to create?". This will be the defined problem to which the design process will be applied.

Next week, we'll dive into the five mindset shifts that can transform your very next presentation.